High School Science Labs and the Digital Divide

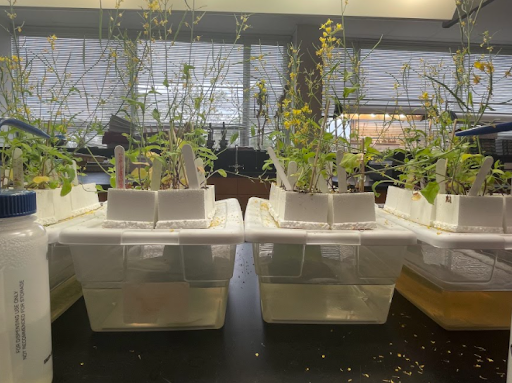

A biology lab at Deerfield to study fast plant growth. Image courtesy of Gabriella Rodriguez.

November 1, 2021

In school or behind a screen, experiments, or labs, are imperative to high school sciences. Labs have long been utilized for their versatility and functionality in classrooms. Whether they are physics demonstrations on projectiles, chemistry studies in titration and concentration, or biology analyses of plants and microorganisms, labs offer students a direct look at their course material in action. Experiments are a crucial way to enhance learning, apply class concepts, and teach students how to conduct research and investigations. Moreover, they cultivate skills such as collaborative group work and communication, and they can even be enjoyable. It is essential that science classes include labs in their curriculums, but questions arise about the best way to implement them.

With the transition to remote learning in the 2020-2021 school year, science teachers needed to adapt to the situation and continue to provide lab experiences for their students, or at least their closest replacements. Ms. Diane Kuai, a chemistry and biology teacher at Deerfield, had to modify her labs to support them for her virtual classes. During the remote year, Ms. Kuai teamed up with other science teachers at DHS to film videos of themselves conducting experiments. Apart from a remote setting, these labs did not need modifications, so students performed them as they would in-person and modeled what they saw in the videos. For example, as part of a lab studying light, Ms. Kuai and the team shipped packages to students with diffraction gratings. Students taped these gratings over their phone screens, and by pointing their cameras at a light source, the gratings split the light into its component parts. This enabled the students to observe the continuous spectrum, a direct application of the material that they learned in class. While this experiment was a success, others were more difficult to coordinate. “[Shipping] was less frequent because of the logistics. We couldn’t ship acids to the students at home or other hazardous chemicals,” Ms. Kuai explained. Since students could not access these supplies, simulations presented another solution. Thus, teachers implemented more virtual labs as their most optimal substitutes.

This shift had a marked impact on students. Senior Anna Choi, who took chemistry during remote learning, had to conduct multiple experiments in a digital setting. “My experience in taking chemistry in remote learning was definitely different from the other experiences I had taking science classes at Deerfield. My teacher did use a lot of virtual labs and most of them were on websites like pogil.org, or Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning,” she said. The value of virtual labs became increasingly apparent during remote learning, where they were among the few viable alternatives to in-person labs. Furthermore, these labs can be restarted with a single click, offering as many repetitions as students need for practice and flexibility. Virtual experiments also avoid many unwanted variables—such as sudden changes in environmental conditions or students following directions incorrectly—that cost accuracy, time, and resources for in-person labs. The benefits of virtual labs extend further, as some simulations offer what in-person labs cannot. Ms. Kuai elaborated, “One simulation I use in chemistry is a “build-an-atom” simulation, where students can drag and drop protons, neutrons, and electrons to make atoms. We wouldn’t be able to do this in a lab.” Such interactive digital representations of otherwise impalpable objects, like atoms and molecules, allow students to explore them in greater detail.

Despite their advantages, virtual labs can only replicate so much of the in-person lab experience. They have difficulty providing the interaction and communication between lab students, features that are critical to experiments. Choi described her experience with group work in virtual labs, recalling, “We often worked on these online labs with a lab group, and although it was nice to have labs, it was hard to collaborate with other students on Zoom calls, especially because we all worked at different paces.” While video calls allowed for communication, any number of interruptions—from repetitive muting and unmuting to poor internet connection—could hinder the conversation flow. This problem became particularly apparent when students constantly had to collaborate on the experiment steps and discuss questions. In addition, when they were distanced from each other, students frequently advanced through the labs at different speeds, which created a disconnect between them and proved detrimental to group interaction.

Simulations may also lack the tactile and stimulating nature of in-person labs. “Sometimes it can give you access to things you can’t otherwise do, but it’s less hands-on than, say, a wet lab where you mix chemicals to see what happens,” Ms. Kuai mentioned. “I obviously missed—and I think the students missed too—the hands-on aspect of labs. Simulations are nice and quite interactive, but they’re still on a screen, so it’s a little more limited.” This “hands-on aspect” of in-person labs engages students with the material. More so than virtual labs, in-person labs elucidate the course information by applying it in a tangible way. As a result, students often better comprehend why they are performing the experiments.

With the return to labs in the building, science students at Deerfield can now thrive as they did before their year of remote learning. Additionally, they can take part in more natural and productive group conversations. “It is much easier to talk and work on the in-person labs with other people than it was to on Zoom calls,” Choi said. She observed the notable contrast when she compared the two types of labs, having worked with both. “Now that I’m back in person, I see the clear difference between the in-person labs and the online labs. The in-person labs are much more enjoyable, as they are hands-on, and we can actually first-up see how they incorporate class material,” she explicated. Ms. Kuai also found that the transition back to in-person labs has been best for the students. “Nothing really replaces the in-person lab and doing the procedure yourself, because that way you’re more in tune with what’s going on and you understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. I think in-person labs are more effective,” she concluded.

In-person labs are back for good, as their qualities are indispensable to student learning. At the same time, virtual labs have proven valuable in several respects, so they can remain and supplement the in-person lab experience. “I use some simulations no matter what, even though we’re in-person this year, because I really see the benefit of them,” Ms. Kuai explained. Joining the interactivity, engagement, and communication of in-person labs with the extensive capacities of virtual labs, science students at DHS can expect enriching experiments in the future.