District 113 Has a Budget Deficit. Where’d all of the Money Go?

December 16, 2021

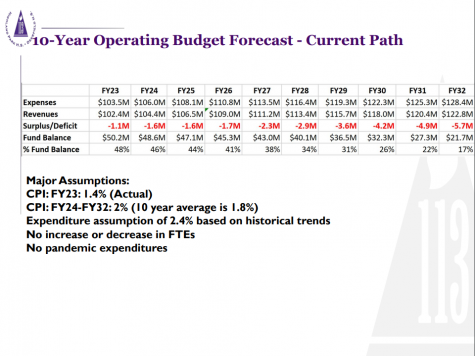

In early October, Deerfield and Highland Park families received a pamphlet summarizing their school district’s financial situation. The outlook was, to say the least, bleak. What they found out was that according to the administration, District 113 faces a “structural budget deficit.” That is, the schools’ expenses outweigh their revenues, and this imbalance will persist for the foreseeable future. Moreover, the master facilities plan—a list of capital projects and infrastructure repairs that the district plans to undertake—turned out to be a nearly $200 million bill that appears impossible to foot in the status quo.

In fiscal year 2020, the district made $2.5 million in returns on investments, while the fiscal year 2021 resulted in a return-on-investment of only $150,000. This decline was due to a nosedive of interest rates on CDs, which are loans to a bank, with 2021 rates being between 21 and 24% of what they were a year prior. Assistant Superintendent for Finances Ali Mehanti explained that the budget deficit has many causes. On the one hand, he points to the aforementioned drop in interest rates. On the other hand, expenditures increased as well because of what Mehanti called “too many variables.” At the moment, though, the principal culprit appears to be the two million dollar revenue loss from the fallen interest rates, and Mehanti believes it will be a long time—perhaps four or five years—for them to return. “In my five year projections, I don’t have interest rates going up,” he said. At the same time, President of the District Educators Association and AP Economics teacher Jerold Lavin is concerned with the district’s financial projections of the returns of these investments over time. He points to the fact that the district is making long-term projections by comparing the recovery of the economy to the COVID-19 crisis with the recovery of the economy after the 2008 global recession. He is not wrong: Mehanti, in defending his projections, said, “No one has a crystal ball, but if you look back at 2008, when the economy crashed, the same thing happened and it took about five, six years for it to spike back up.” In Lavin’s eyes, since 2008 was a result of structural problems in the bond market, while COVID-19 was not a structural but external problem, their recoveries cannot be compared. Thus, Lavin is concerned that the district is making long-term projections based on Mehanti’s comparison of the two. Another reason that Mehanti does not include a potential early recovery in his projections is disconnected from interest rate forecasts entirely—to an extent, he feels it would be irresponsible. Return-on-investment is a variable source of revenue, so while it’s possible to consider the budget “balanced” assuming high investment revenue, it could still drop again. Even if it might seem unreasonable to assume a late recovery to the recession, Mehanti thinks it is safer not to rely on investment revenue when balancing the budget.

Another concern of the district is preventing the depletion of its reserve fund. However, Lavin sees this as a way to kill two birds with one stone. The district has $50 million invested for a “rainy day,” Lavin noted, but he doubts that all of that is really necessary for any reasonable emergency. Bond-rating agencies decide if an institution’s bonds are a good enough investment through a rating system, and they make this decision based on a number of factors. Lavin believes the district’s rating won’t be affected until the balance drops to around $25-28 million, meaning the district is reserving $25 million it doesn’t need for the future. Whether Lavin is accurate or not, District 113 school board member Rick Heinemann noted that a depleted fund balance would garner significantly less return-on-investment than a $50 million balance would. Still, Lavin asserted that the district should be allocating some of this extra money towards infrastructure and other problems the district projects to cause a deficit.

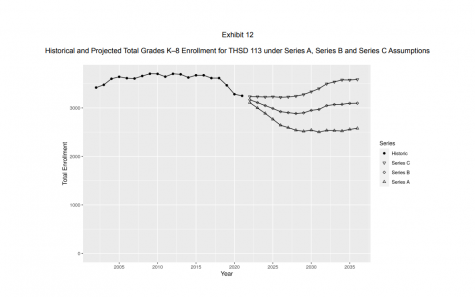

Along with this, Lavin is critical of the district’s projections for expenditures. When the administration presented its budget projections in the event of each solution in September, the district assumed no change in FTE, or full-time equivalents—essentially, the amount of full-time employees requiring pay was assumed to remain the same. Lavin asks, “Why would we be paying the same for staff if we have significantly less kids?” Indeed, over forty teachers are scheduled to retire over the next four years, and the general consensus among both Lavin and the district is that not all positions will be replaced. Further, Heinemann explained that in order to address the budget deficit, one of the essential questions to ask was, “Do we have to rightsize the district from a staffing position?” Defending the choice, Mehanti explained that the administration simply wanted to present projections for three scenarios by holding other variables constant—it is not possible to pin an exact number to the decline in FTE. Nevertheless, on account of the savings omitted by assuming no reduction in FTE, there is no denying that the district’s budget projections in September looked at least slightly bleaker because of this decision.

However, the notion that enrollment will decline contradicts projections of government and private analysts, teachers, and other recent studies in the District 113 area. District 112 has a demographic study on the area’s districts that shows the opposite, with a steady rise in enrollment in many cases. In that study, DHS’s enrollment is projected to remain almost exactly the same in 15 years given the current anticipations for residential development. The combined enrollment of the two high schools would decrease by 154 students in current projections—significantly less than implied—but might increase by 337 if development is more than projected. Most importantly, all projections involve an initial decrease in the next few years but a long-term upward trend. This both complicates the idea of maintaining the FTE initially and of long-term decreases in enrollment.

Notwithstanding any problems with the District 113 administration’s assertions, the discussion then turned toward potential solutions. Or, Heinemann said, the discussion came to the forefront within the community. “Even before I was on the board, the district was talking the financial difficulties for almost a year, and the facilities for longer than that,” Heinemann said, adding, “It should not have been a surprise [to the community], though I understand why it would be, that we had to grapple with potential solutions to these issues.” He explained that the community turned its attention to the issues because of the shock associated with the proposal to consolidate Deerfield and Highland Park high schools, saying, “It was our fiduciary duty to at least explore whether or not closing one of the schools was an option,” even though the district has since eschewed that measure. Now, the district has started what Heinemann called “the hard work” of cutting costs, which entails a discussion about personnel. “Since the vast majority of the spending in the district is on people–we’re talking about salaries, benefits–we have to, very much, ask, ‘Do we have the right amount of faculty? Do we have the right amount of administrators?’” explained Heinemann. Lavin pointed to some new personnel that he sees as superfluous as an obvious starting point. Specifically, he mentioned what he calls a new “PR Department” of two people in the district office, costing the district $250,000 in less than two years. Again, he asked why the administration actually increased spending with these hires when it also projects a fiscal crisis.

If retrenchment fails to balance the budget, the district may need to resort to the often-dreaded measure of raising property taxes via a referendum. At the moment, however, Heinemann said, “The way I look at it is that there is a large number of things that the district needs to do before something like that is put on the table.” Indeed, before the administration can make any drastic changes to the district, it must finally deal with its financial problems responsibly.